Dans Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs, Johann Hari lays bare the unintended consequences of the global War on Drugs.

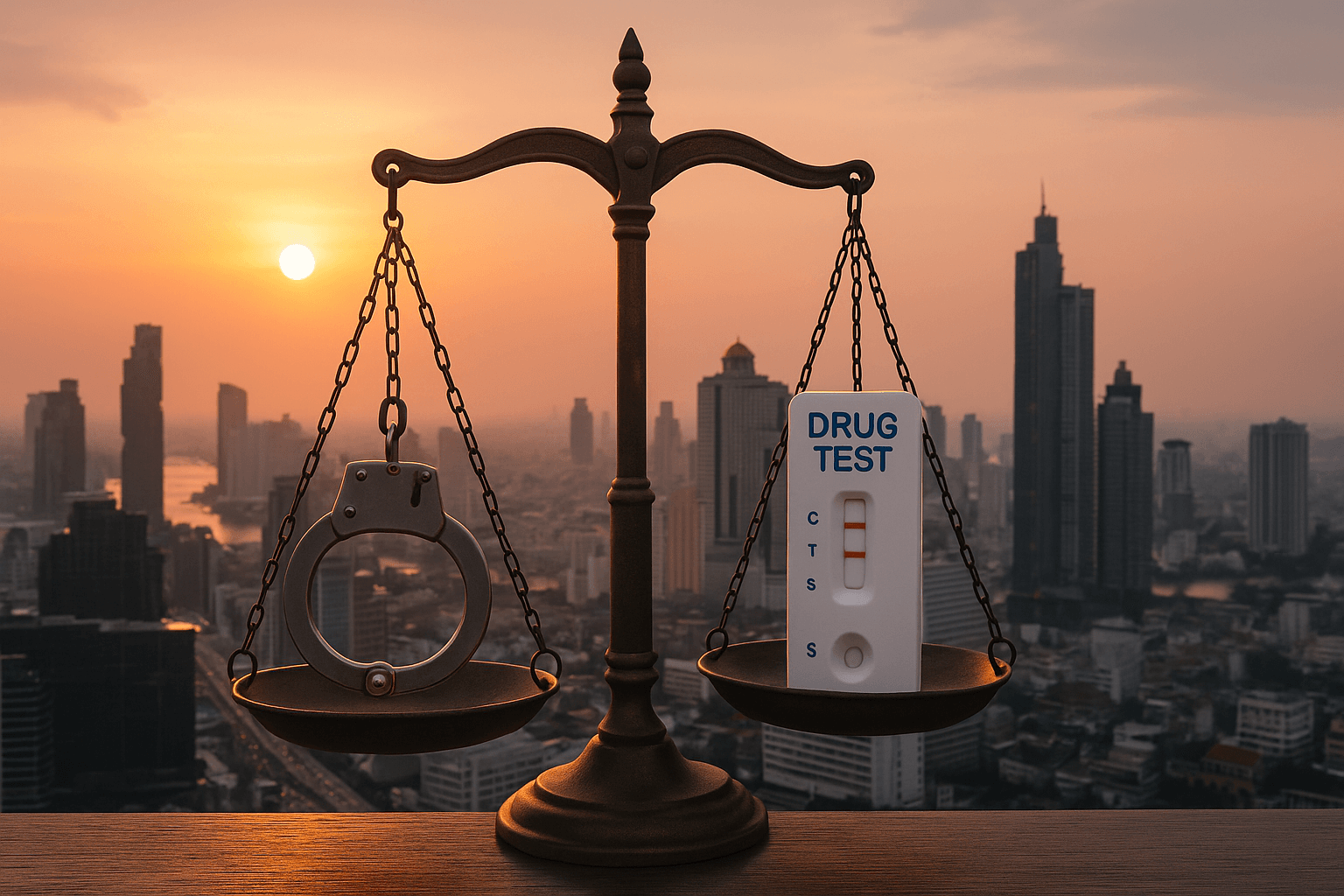

He argues that punitive policies often exacerbate the very problems they aim to solve, from driving drug use underground to fueling the rise of more dangerous substances. Bangkok, with its long history of strict drug enforcement, provides a compelling case study for Hari’s insights.

This post explores how Bangkok’s experience with the War on Drugs mirrors global patterns, highlighting the consequences of punitive approaches and the need for harm reduction strategies.

The Origins of Thailand’s War on Drugs

Thailand launched its War on Drugs in 2003 under Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, targeting methamphetamine (yaba) with mass arrests and crackdowns. The campaign’s initial results were dramatic:

- Reduction in Visible Drug Use: Methamphetamine use reportedly decreased in the short term.

- High Profile Raids: Thousands of individuals were arrested, and significant quantities of drugs were seized.

However, Hari’s analysis of similar campaigns worldwide suggests that these early successes often mask deeper, long-term issues.

Unintended Consequences:

1. Increased Violence: The crackdown led to extrajudicial killings, with over 2,500 deaths reported in the campaign’s first year alone.

2. Push into Underground Markets: Fear of enforcement drove traffickers and users deeper underground, making the drug trade harder to detect and regulate.

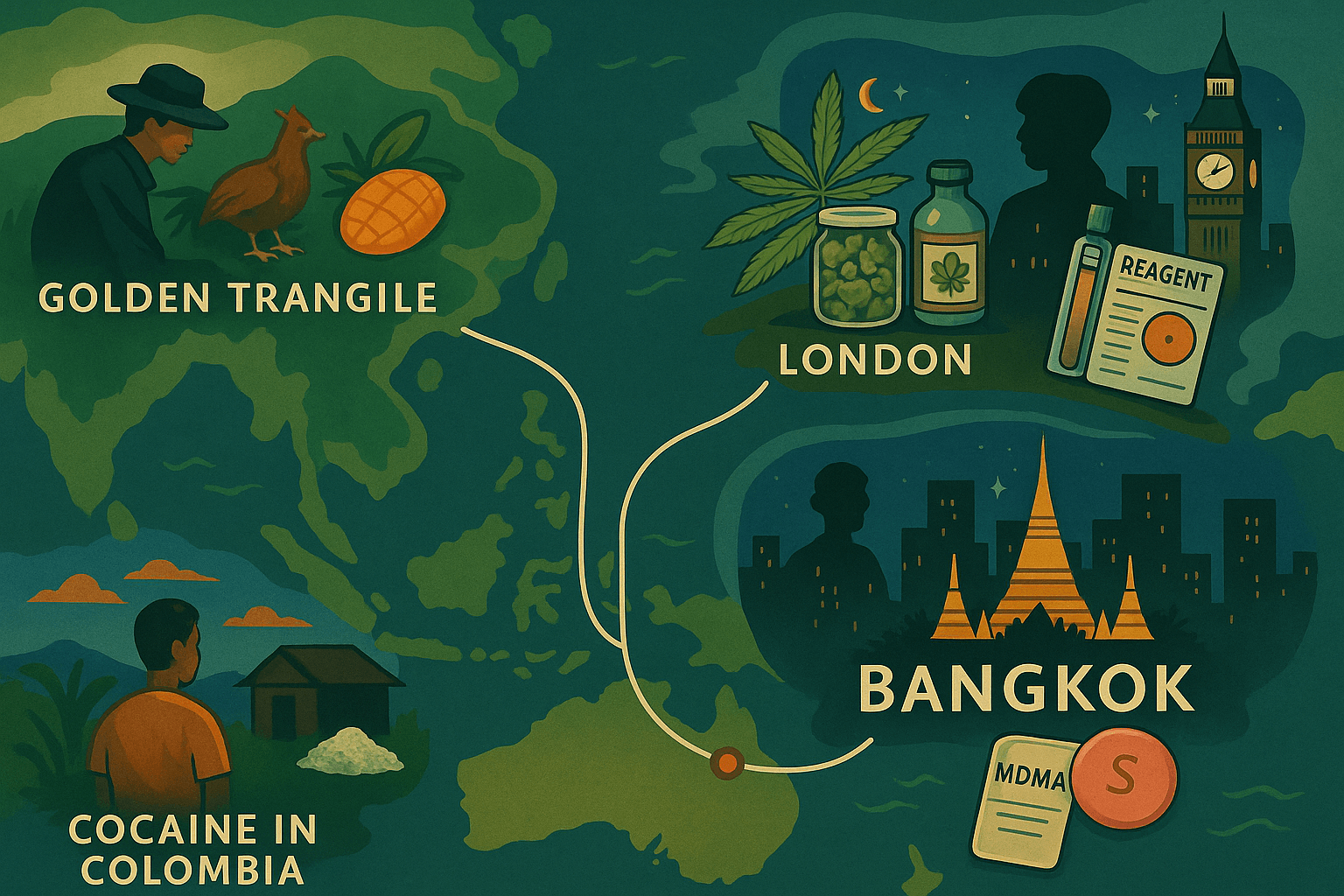

3. Rise of Synthetic Drugs: With methamphetamine production targeted, traffickers shifted to new synthetic drugs like crystal meth and synthetic opioids, which are harder to track and often more dangerous.

The Parallel Global Patterns

Hari’s work reveals how these consequences are not unique to Thailand but are part of a global pattern:

- Increased Potency: Just as the War on Drugs in the U.S. led to the rise of crack cocaine and later fentanyl, Thailand’s crackdown on yaba paved the way for high-purity crystal meth and synthetic opioids.

- Targeting the Vulnerable: Punitive policies often disproportionately affect low-income individuals and marginalized communities, who are more likely to face arrest and imprisonment.

- Public Health Crises: Fear of enforcement discourages users from seeking medical help, exacerbating overdose rates and the spread of diseases like HIV.

Example from Hari’s Research: In the U.S., the criminalization of heroin pushed users toward fentanyl, a more potent and deadly alternative. Similarly, Bangkok’s focus on methamphetamine has allowed synthetic opioids to gain a foothold in the city’s drug markets.

Bangkok’s Current Landscape: A Snapshot

Bangkok today reflects many of the unintended consequences Hari describes:

- Adulterated Drugs: Synthetic opioids like fentanyl are increasingly found in MDMA and cocaine, raising overdose risks.

- Stigma and Fear: The stigma surrounding drug use, reinforced by decades of punitive policies, prevents open discussions about safety and harm reduction.

- Persistent Trafficking Networks: Despite enforcement efforts, Bangkok remains a major transit hub for drugs produced in the Golden Triangle.

Statistique clé : A 2023 report by the UNODC found that Thailand accounted for over 50% of Southeast Asia’s methamphetamine seizures, yet use continues to rise.

How Harm Reduction Can Address These Consequences

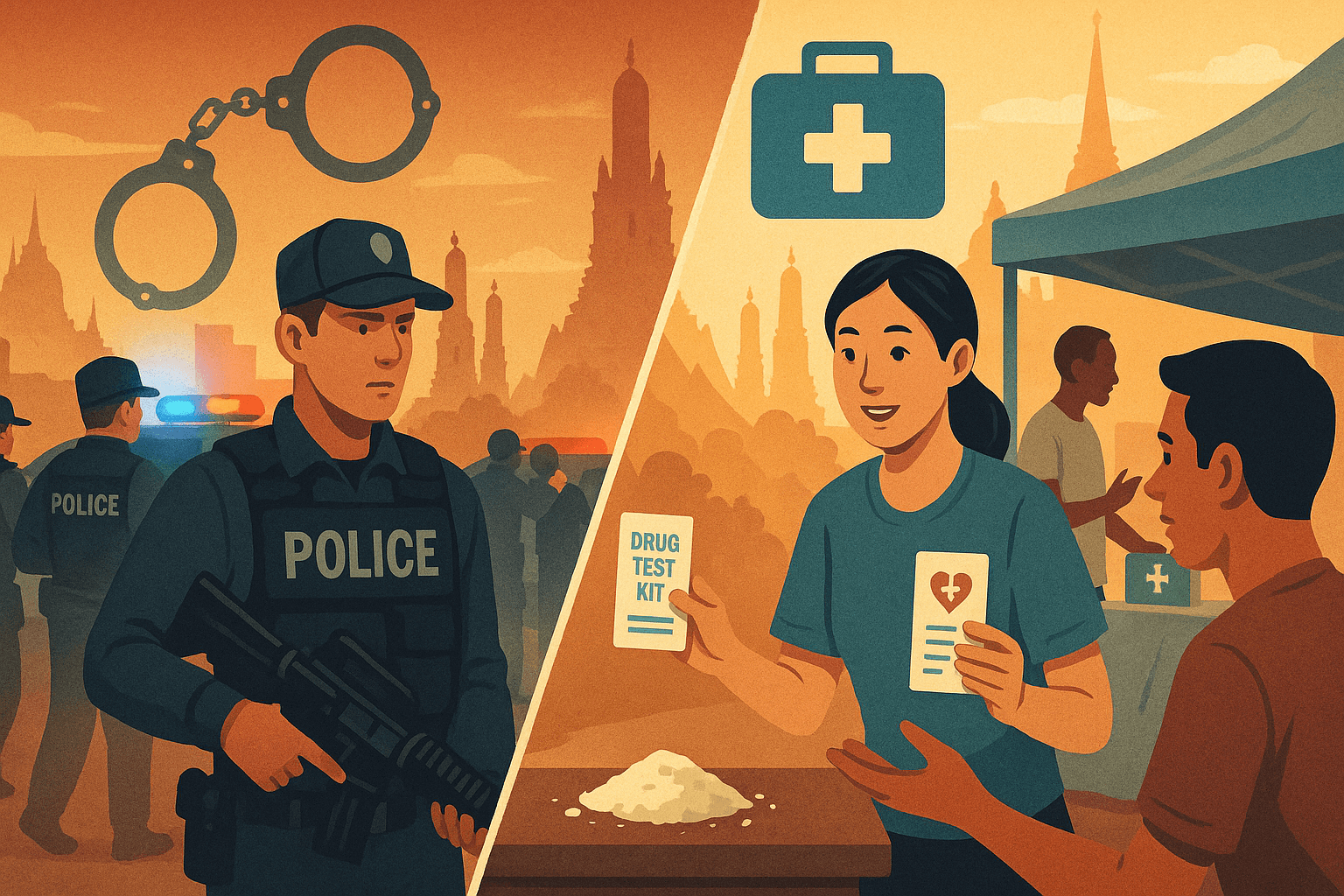

Hari advocates for harm reduction as a way to break the cycle of punitive enforcement and unintended harm. For Bangkok, this means shifting the focus from punishment to education, safety, and support.

Strategies for Bangkok:

- Make Drug Testing Accessible: Providing drug testing kits through platforms like Happy Test Shop can help users identify adulterants and avoid dangerous substances.

- Reduce Stigma: Public campaigns should frame drug use as a health issue rather than a criminal one, encouraging users to seek help and use harm reduction tools.

- Decriminalize Personal Use: Decriminalization, as seen in Portugal and Canada among others, reduces fear of enforcement and allows users to access support services without legal repercussions.

Why Bangkok Needs a New Approach

Hari’s analysis shows that punitive policies alone cannot address the complexities of drug use and trafficking. For Bangkok, adopting harm reduction strategies can:

- Protect Lives: Reduce overdose deaths and hospitalizations by encouraging safer practices.

- Disrupt Trafficking: Reduce demand for adulterated drugs, forcing traffickers to adapt.

- Foster Community Trust: Build a culture of openness and support that prioritizes public health.

Global Insight from Hari: “The opposite of addiction is connection.” By focusing on harm reduction, Bangkok can move from a punitive system to one that fosters connection, understanding, and safety.

For a more historical perspective on how Southeast Asia’s policies shaped today’s environment, read our companion post on Peter Jenkins’ work in this article here.